What does it mean to be a smart city? Though the definition is certainly evolving and will continue to do so, it’s important for municipal leaders and advocates in aspiring smart cities to begin developing a good answer to this basic question.

This year’s Smart City Challenge from USDOT generated a tremendous amount of excitement and also forced cities to step out of their comfort zones, work across departments and put together a coherent business plan for their ambitions. Overall, as we noted in our last post, as we read through the applications, it’s still really hard to put a finger on precisely what a smart city is right now, and what it means to be one.

One of the first tasks for our Smart City Collaborative will be to start defining that question.

The Smart City Collaborative is our national, multi-city collaborative with Sidewalk Labs to help cities use technology to meet their pressing transportation challenges. Cities in the collaborative will join working groups focused on one aspect of a smart city and collaborate to develop pilot projects, share successes and failures, and engage with one another to come up with new, creative solutions to their unique problems. Find out more and apply here.

At Transportation for America, we start with the concept that a smart city uses technology to discover where people are going and where they want and need to go, and learns from that information to create safer, more efficient, and affordable transportation options that accelerate access to opportunity for all of their residents.

While technology is important, it’s only a tool in the toolbox. It’s the means, not the ends. But what ends? What goals? Every conversation about smart cities should start with outcomes and purposes first, such as:

- Engaging a wider range of our community and solicit feedback from people who might have been left behind in the past.

- Building a more efficient city that gets greater returns from each investment.

- Developing a more equitable and inclusive city with improved access to opportunity for everyone.

- Understanding as much as possible about residents’ needs, in order to craft solutions to better meet them.

- Testing and failing and learning from mistakes quickly to take charge of their destiny.

Technology is a part of helping cities reach those goals, but it needs to be wielded thoughtfully and intentionally. As Allison Arieff said in an interesting New York Times piece recently, “Are we fixing the right things? Are we breaking the wrong ones? Is it necessary to start from scratch every time?”

Cities don’t need to have social media or a fancy app to meaningfully engage their residents. There are still proven ways to improve transportation options for more people without on-demand transit or new mobility apps. Cities can smake safety for people walking or biking a high priority immediately without new vehicle-to-infrastructure technology or smart traffic signals.

With these thoughts in mind, here are four things starting to emerge as core aspects of a smart city.

Smart cities are more equitable and inclusive

Smart cities ensure that new technologies are used to accelerate access to opportunity for all residents — not just certain segments of the population. The most successful cities are good at creating opportunity for people of all incomes. This starts with the city driving the discussion and ensuring low-income residents and communities of color, and especially the unbanked and digitally disconnected, are always included in the conversation. It’s critical that any new developments or technologies reduce the divide between the transportation haves and have-nots.

Smart cities use technology in a way that brings benefits to every resident — regardless of age, ability, income, or zip code.

Smart cities work closely and transparently with constituents

Engaging more people in more productive ways is a bedrock of better, more inclusive decision-making. Like the process of creative placemaking (chronicled in depth in this T4America resource), when residents are involved in meaningful ways in the process, they’re not only more likely to feel ownership of the outcome, but the end product is almost always better.

Face-to-face, old-school community meetings should still be a staple of any city’s efforts, but new technologies offer the chance to receive feedback from people in new ways; real-time feedback and data on everything from air or noise pollution to dangerous intersections to places where transit service is lacking.

Smart cities are dealmakers who aren’t afraid to take risks

Cities that sit on the sidelines while these disruptions take place will see their cities shaped by others, without their feedback, and very possibly without the best interests of all of their residents in mind.

Cities need to learn how to drive the discussion and be the dealmakers. The old 20th century regulatory framework no longer applies. Cities need to make deals and negotiate vendors and providers on their terms and ensure that these changes enhance transportation choices for everyone.

A cultural shift within municipal governments will also be necessary; political and executive leadership will need to be willing to test and fail. As former Chicago and Washington, DC transportation head Gabe Klein illustrates with real-world examples in his terrific short book Startup City, cities need to think more like flexible, nimble tech startups than lumbering bureaucracies.

A cultural shift within municipal governments will also be necessary; political and executive leadership will need to be willing to test and fail. As former Chicago and Washington, DC transportation head Gabe Klein illustrates with real-world examples in his terrific short book Startup City, cities need to think more like flexible, nimble tech startups than lumbering bureaucracies.

Cities need to be willing to launch pilot projects, test ideas, learn from those experiments, and be willing to share the results even when they fail. Big companies, universities, and startups across the country are developing new pilot projects for first/last-mile solutions, automated vehicles, urban delivery technologies, new parking platforms, and much more. Smart city leaders are the ones that proactively engage these groups to help solve their major challenges to accomplish their city’s goals. Innovation and solutions are coming from every direction today.

Smart cities know what data to collect and how to use it

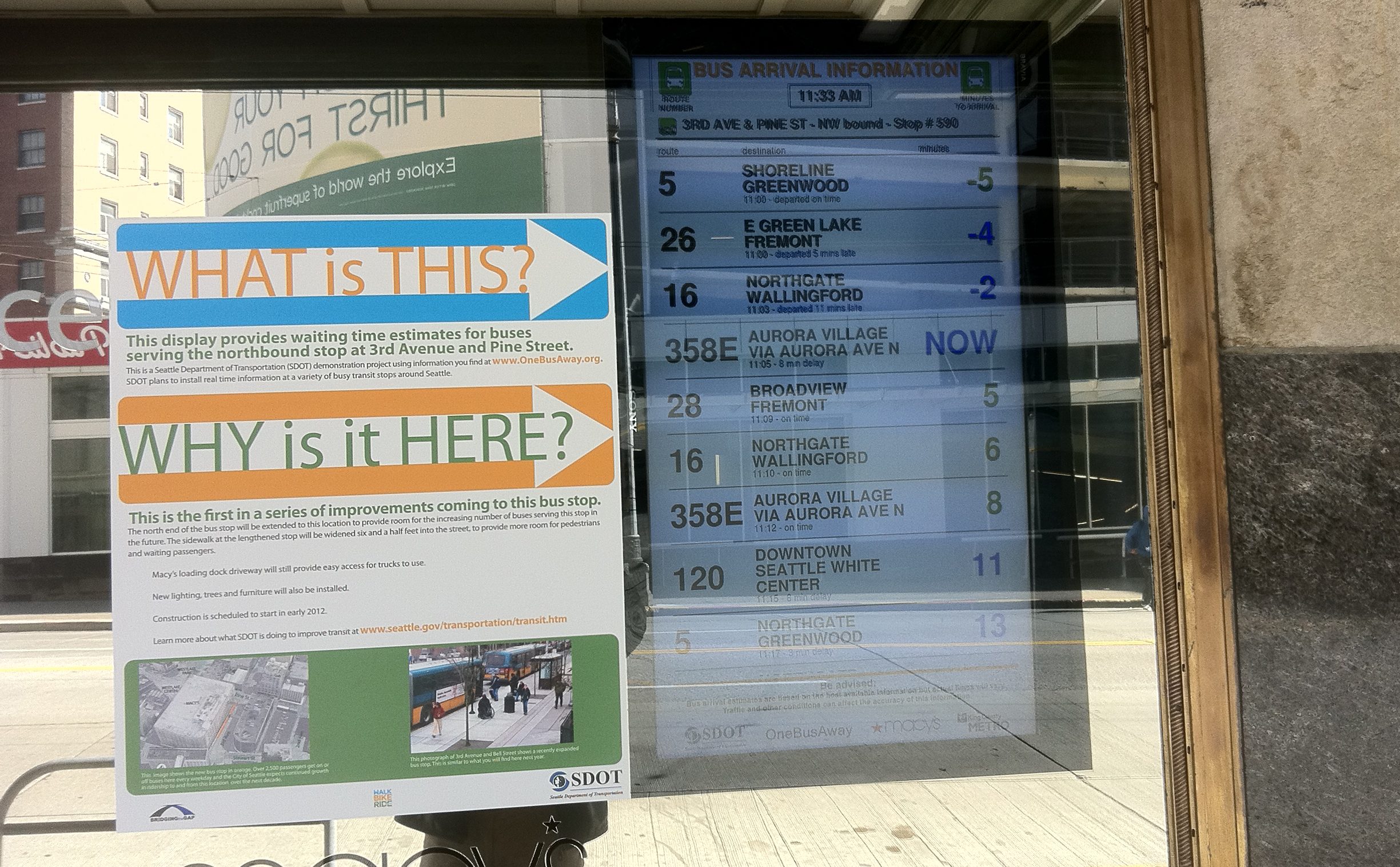

It’s important that cities know what’s happening in their communities and on their networks, and that means collecting data — lots of it. That information can come from a variety of sources; from residents, sensors, cell phones, vehicles, cameras and much more. Cities need to have a complete and holistic picture of what’s happening in order to make the best possible decisions.

Cities must have a process in place for analyzing and understanding their data in order to accomplish their goals. Only then will they begin to know how to use it to inform their day-to-day operations and long-term policy goals. And this is the underlying goal that can often be lost in the “smart city hype:” finding ways to make more informed and educated decisions to help a city become what they want to be.

As urban populations continue to grow, many of the problems of yesterday and today – congestion, economic inequality, pollution – grow with them. There are ways to leverage technology and better data in order to combat these challenges in new and more efficient ways and be vibrant, attractive, inclusive, prosperous places to live.

This post was written by our Smart Cities team of Russ Brooks, Robert Benner and Steve Davis.

Comments (1)